A Roadmap for the Uninitiated, Part One

On the origins and early decades of jazz. Part one of an ongoing jazz history series.

Jazz is a fundamentally American music. It is considered by many to be the first great contribution from American culture to global society. Today when we think of jazz, we think largely of its highlight moments. We think of the Roaring 20s, swing dancing, the romanticized notions New York City, or the heydays of New Orleans. While all of these things are central elements to the legacy of jazz, it is also important to acknowledge the full story of jazz.

To truly appreciate jazz, we must also understand it has a history fraught with many of the grim realities that underpin the story of America itself. It should be understood that as an American art form, jazz is fundamentally African American music. The story of jazz is also the story of Black History in America. It is the story of liberation from slavery, the battle against commodification without profit, the advancement of the Civil Rights Movement, and the ongoing struggle to confront and overcome the destructive legacy of white supremacy in the United States.

PRE JAZZ AND THE ORIGINS OF JAZZ MUSIC

Jazz music finds its origins in American slavery. Though the practices of slavery had already been underway in the Americas since the arrival of Columbus in Hispaniola in 1492, the slave trade in the United States is considered to have its significant starting point in 1615. An estimated 12.5 million Africans were taken hostage and sold into slavery over the 400 year history of the slave trade. Countless others were born into slavery on American shores. Having been stripped of everything else, enslaved Africans brought only their cultural, religious, and musical traditions with them to the New World.

African musical traditions were unlike anything heard in European music at that time. In general, the metronomic sense, overlapping call-and-response, off-beat phrasing of melodic accents, the dominance of percussion, and polyrhythms were all unique and distinctive elements of African musical traditions that did not exist in the European musical tradition prior to the slave trade.

The utilization of blue notes and syncopation in early African American musical traditions was a revelation to American music. Early African American music had a profound impact on every major American musical tradition to follow, resulting in a global influence over time.

The sense of rhythm in African musical traditions was so distinct and pronounced that slavers were fearful that their captives could communicate through rhythm, and coordinate rebellion using drums. As a result, African drums, drumming, and African music were outlawed.

Deprived of their drums and musical traditions, the enslaved Africans created new musical traditions that were uniquely African American. Music served as a means of release and self-expression for countless enslaved African Americans forced to live in captivity, and to endure the crushing indignities, torture, and relentless demoralization of life as a slave.

Work songs and field hollers emerged as a form of functional music. In half-sung, half-shouted language, the music set a working tempo, or called for water or help across long distances in the fields. Outside of labor, music was typically only allowed in the context of religious assimilation, especially in the Puritanical British colonies.

The push for assimilation meant that most early African American music had a Christian religious connection, incorporating the European practice of “lining out” psalms, and lyrics calling for mercy and salvation. The first all-Black churches appear to have developed near the end of the 1700s. In these churches, hymns and spirituals replaced the tradition of lining out psalms. Choirs and congregations sang spirituals in the call-and-response form, alternating solo verses with refrain lines.

In the French and Spanish-controlled colonies there was a comparatively less repressive environment than in British colonies. The French and Spanish demanded less cultural assimilation from their slaves, and had a less restrictive social code than the British.

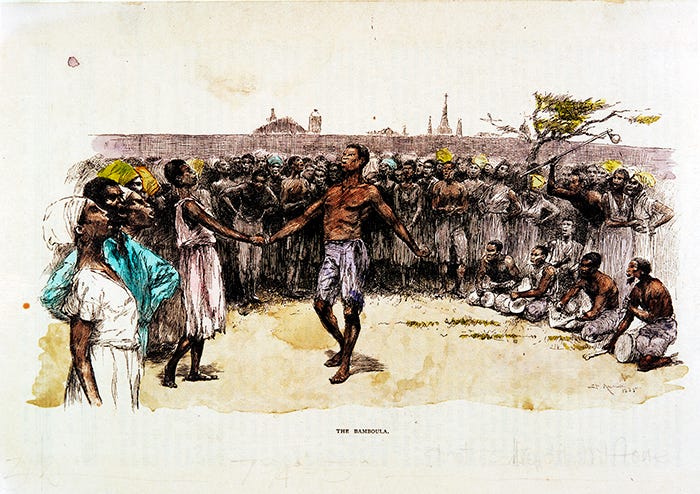

In Spanish-controlled New Orleans, the slaves were allowed to have Sunday afternoon off in observance of the Catholic day of rest. During these times, many would congregate in the out-of-city-proper park known as Place Congo (now Louis Armstrong Park). It was there that the origins of jazz music would take root.

For these gatherings and performances, the ban on drumming was relaxed and the slaves were allowed to dance, play African-style drums such as ndungu and bamboula, and briefly reconnect with their cultural traditions. Common instruments at these gatherings also included the four-string banjo (an instrument imported by West African slaves from Senegambia), and the kalimba or mbira, which were derivative of the African thumb piano.

In these instruments, we can see a precursor to the early jazz rhythm section. Dance would remain a central element of jazz culture as well. Over time, these gatherings would draw spectators, including prominent local figures such architect Benjamin Latrobe. Performances in the park continued well into the 1880’s, and musical traditions continued to intermingle, with the local Creole and Spanish cultures contributing to the early Latin influences on jazz.

THE RISE OF MINSTRELSY

The abilities of African American musicians became lauded throughout the United States, but the musicians themselves would be culturally removed from earnest appreciation. Black musicians were more so regarded as a sideshow than as legitimately skilled and innovative musicians or composers. The story of America’s first African American music star, Thomas “Blind Tom” Wiggins, exemplifies this era of American entertainment history.

Wiggins was a remarkable piano prodigy. By the age of 4, Thomas could imitate sung melodies on the piano, and by age 8, his talents were being monetized by slave-owner General James Neil Bethune. Thomas Wiggins was blind, likely autistic, and suffered long-term cognitive damage resulting from being isolated for much of his childhood due to medical quackery. After abolition, Wiggins was made a ward of Bethune because of his disabilities.

“Blind Tom” was promoted not as a prodigy or virtuoso, but rather as an “idiot savant,” and his performances were considered comedic, made to include degrading stunts and sideshow acts, all while playing virtuosic piano. At the height of his fame Thomas Wiggins’s performances would bring in as much as $5000 per show, which by today’s standards would be about $100,000 per night, none of which went directly to Thomas.

Though there was clearly an appreciation of Black music, and emulation among white musicians, culturally, white America could only enjoy Black music and culture under the context of white ownership, and through a perceptual lens that would support the morality of white dominance in society. So long as the skills of the musicians could be trivialized, the performers degraded, and the profits all directed to white hands, then it was acceptable or even preferable entertainment.

To accept Black performers as innovative, highly skilled artists, rather than sideshow “magic acts,” would have fundamentally challenged the legitimacy of the sociopolitical structure of the nation. This exploitive form of appreciation continued for decades in many areas of American culture. Perhaps the most profound example is the story of Thomas Wiggins, but it was also central to Minstrelsy.

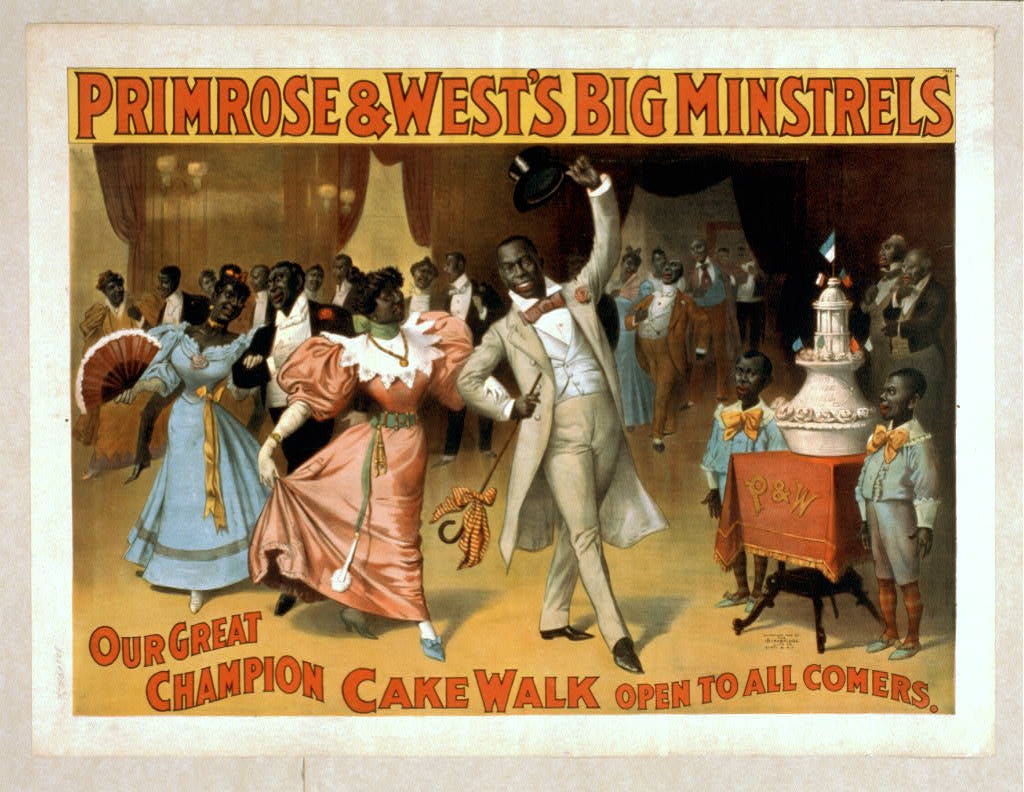

Minstrel shows featured the use of blackface, overtly racist themes and offensive racial humor. Early minstrelsy saw all white performing troupes in blackface singing songs modeled after spirituals, and performing comedy skits centered around degrading, racist characters.

Starting in 1832, Thomas Dartmouth “Daddy” Rice took his Jim Crow act from New York to London, creating a craze for minstrel song and dance. Through the success of Rice’s shows, Jim Crow became a stock character in most minstrel shows, along with the Sambo, Zip Coon, Mammy, and Hannah characters. All of these characters came with their own associated stereotypes, and reinforced fundamentally negative and dehumanizing interpretations of African American culture.

Minstrelsy and its mocking, demeaning depiction of Black culture, produced enduring racist themes. These stereotypes give an insight into the racist values that underpinned American society and how they were used to justify white dominance. By 1838, the term "Jim Crow" was being used as a collective racial epithet for Black people. Though today the term is more commonly remembered in reference to the repressive laws of post-slavery America through the late 1960s, at it’s inception, it was a term weaponized against Black people, and supporting those institutions of racism.

Echoes of Minstrel themes and characters still persist within modern American culture and society. This has been highlighted by the modern day controversies surrounding the use of blackface as a comedic device in films and television, and the continued use longstanding minstrel characters, such as the Mammy character and (now retired) maple syrup icon, Aunt Jemima.

The themes of Minstrelsy can also be found in American politics, with a notable example being when Ronald Reagan employed a mixture of Mammy and Hannah themes in creating the falsified “welfare queen” character used on the campaign trail in his 1976 presidential campaign, and in subsequent elections in the 1980s. The welfare queen epithet was later used to garner support for cuts to social welfare programs, and remains in use as a rhetorical device in the modern Republican party.

THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY AND THE BLACK MINSTREL CIRCUIT

Despite the negative and damaging cultural context, it was ironically through Minstrel shows that African American music became intertwined with the political movement to end slavery. Minstrelsy rose to its greatest popularity through the abolitionist movement. Abolitionists coopted the format as a vehicle to openly critique government policies and advocate for abolition within the safety of character, finding the shows to be a more effective approach than pamphleteering.

White audiences were able to remain in their comfort zone and engage with a purportedly genuine depiction of African American life, behavior, singing and dancing that took place on rural plantations. Songs supporting abolition emphasized the suffering of slaves rather than contentment on the plantation, with one notable song featuring a slave master being sent to Hell upon death and made to live the life of a slave.

There was a condescending edge to the abolitionists’ call to pity slaves that evokes thoughts of a “white savior” complex, and the abolitionist performances still retained all the racist trappings of Minstrelsy. While the United States was ready to end its relationship with slavery, the concept of white supremacy was still deeply ingrained in American culture.

The events of the Civil War followed. With the ratification of the 13th Amendment on December 6, 1865, and the battles that followed to force the release of slaves culminating on June 19, 1865, slavery in the United States had finally ended. With the fall of slavery, Black musicians and performers would eventually see an opportunity for advancement in the Minstrel circuit. Black Minstrel companies toured the United States and Europe, with the performers still appearing in blackface because that was what audiences expected.

Despite their profoundly problematic history, Black Minstrel companies represented employment for actors, dancers, and musicians, and helped popularize various dances that originated in African American culture. Though peak popularity for the shows would wane by 1900, the influence of Minstrelsy continued well into the 1920s, as highlighted by historic film The Jazz Singer (1927), and its several remakes.

The Minstrel circuit gradually evolved into vaudeville, which offered more opportunities for Black performers and fewer pronounced racist themes throughout the show. Legendary blues singers Mamie Smith and Bessie Smith, and many other blues performers found their start in vaudeville.

Urban musical theater also developed out of minstrelsy. Turn-of-the-century New York saw the development of a flourishing Black theater community that included the composers Bob Cole, James Weldon Johnson, Ernest Hogan, and Will Marion Cook. They built many of their works on African American themes, and their compositions served as important precursors to ragtime.

THE RISE OF RAGTIME

Ragtime took the nation by storm from the early 1890s to roughly the early 1920s. For the first time, a specifically African American musical genre entered and dominated the U.S. mainstream, and also achieved notable popularity in Europe. Ragtime found its origins in the Midwest, where Black musicians popularized the form in the saloons, brothels, and social gatherings of St. Louis, Missouri. The first published ragtime composition was “La Pas Ma La” in 1895, written by Black Minstrel performer Ernest Hogan.

The work of Black composer and pianist Scott Joplin was the pinnacle of classic ragtime canon. Joplin managed to get a relatively equitable contract from the Stark Publishing company, and went on to incorporate ragtime within larger, more classically oriented musical forms, including the ballet, Ragtime Dance, and two operas.

White musician and composer Ben Harney released the first manual of ragtime performance, Ben Harney’s Ragtime Instructor, in 1897. Harney’s manual became a household item, and helped to popularize the practice of syncopating rhythms of well-known songs the fashion of ragtime, a practice known as “ragging.”

Harney enjoyed great commercial success and often billed himself as the “Originator of Ragtime,” or more often, the “Father of Ragtime.” Though Harney did a great deal to popularize Ragtime, he was certainly not its inventor. Harney’s false claim, which was published and disseminated for decades, foreshadowed a repeated occurence of white musicians commercializing and claiming credit for styles of music invented and innovated by Black musicians.

Ragtime laid the foundations for the evolution of Harlem stride piano, with artists like James P. Johnson, Luckey Roberts, Willie “The Lion” Smith, and Richard “Abba Labba” McLean advancing the form.

THE RISE OF THE BLUES AND RACE RECORDS

With the wain of ragtime came a more prominent rise for the blues. Ultimately, we can trace the story of the blues from its origins in field hollers, spirituals, and folk ballads. Blues moved onward to the jook joints, circuses, minstrel shows, and vaudeville stages, and finally, to the center of U.S. songwriting in New York’s Tin Pan Alley.

Black composer and trumpeter W.C. Handy incorporated elements of blues and Ragtime into his compositions and created some of the first music that would resemble early styles of jazz. After early successes, Handy moved to New York, where he worked to popularize the blues and devoted himself to the cause of Black music and its recognition.

The first ever recordings of Black musicians were labeled as “race records.” Some of the most notable race records were those of Mamie Smith and Bessie Smith. The tracks, “Crazy Blues,” by Mamie Smith, and “Backwater Blues,” by Bessie Smith showed the early origins of blues and jazz singing, with loosely constructed phrasing, offbeat, syncopated placement of notes and lyrics, and the use of slides, blue notes, and other vocal embellishments.

The monetization structure of race records directed the profit to white ownership, despite the fact that they featured exclusively Black musicians, and were primarily purchased by Black audiences. Today, race records provide some of the only preserved historical recordings of Black innovators in early jazz, blues, and country, despite their exploitive origins.

NEW ORLEANS AND THE BIRTH OF JAZZ

Around 1920, a more pronounced shift from ragtime to jazz came with the rise of New Orleans Jazz, also known as Dixieland. Virtuoso soloists Buddy Bolden and Sidney Bechet were some of the first to revolutionize the form and lay roots for the establishment of jazz as an improvisational, soloist’s art. New Orleans bands used collective improvisation in their music, and found regular work in the night clubs and sporting houses of the city during the early days of jazz.

Jelly Roll Morton emerged as one of the most influential New Orleans pianists and early composers of jazz music. With his characteristic “Spanish tinge,” Jelly Roll incorporated Latin dance rhythms into jazz compositions, showing early signs of Latin fusion that would be integral to later styles such as Bebop, bossa nova, and crossover.

Morton was a “Creole of color,” which meant that he enjoyed a higher social standing than many of his Black musical contemporaries, and had a greater degree of agency in marketing and commercializing his music. Morton would eventually claim to have invented jazz in 1902. While Morton was undeniably on the cutting edge of jazz originators, his claim to ownership was an exaggeration, and considered historically inaccurate. Morton is recognized as the first jazz arranger, as the first to properly notate jazz in a way that proved it could be recorded in sheet music.

As the early jazz scene continued to coalesce in New Orleans, white musician and composer Nick De La Rocca was given the opportunity to record the first commercially-produced and sold jazz record for Victor Records in 1917. The recordings were a great commercial success and were the first exposure many people had to jazz throughout the United States and Europe. La Rocca seized on the opportunity, making the particularly egregious claim that he was, in fact, the originator of jazz music.

La Rocca’s Original Dixieland Jazz Band played Dixieland jazz with a hack-comedy barnyard tinge, imposing the sideshow elements of the Minstrel era onto the New Orleans Jazz idiom. The ODJB told their audiences that their performances were completely extemporaneously improvised, but in reality they were nearly identical every night.

This tendency of claiming extemporaneous improvisation on previously composed and practiced works became a widespread commercial gimmick that many bands employed to impress unwitting audiences, leading to widespread misconceptions – and false supporting claims from musicians – about the song structures and the nature of improvisation in jazz music.

Once again, a white musician would be the first able to popularize, monetize, and attempt to claim ownership of a fundamentally African American art form on the national scale. Though De La Rocca was an unscrupulous appropriator, the success of the ODJB recordings and subsequent demand for jazz bands would also help pave the way for more performance opportunities and widespread acceptance towards Black musicians.

THE GREAT MIGRATION

As performance opportunities in New Orleans started to dwindle and jazz began to find a foothold in the broader United States, the appeal of leaving the racism and repressive conditions of the Jim Crow South increased. Getting out on tour as a nomadic band, or emigrating to less hostile conditions in the (still heavily discriminatory) urban centers of the North was a chance many musicians chose to take, and a great exodus from the South had begun.

While some musicians remained in New Orleans, significant figures of the New Orleans jazz scene joined in the Great Migration, finding notable landing points in Chicago and New York. Some musicians, such as Sidney Bechet, spent long stints in Europe. In Europe, Bechet could enjoy less hostile social conditions and jazz celebrity in France and the United Kingdom. Jazz pioneers like Bechet helping bring jazz to Europe and influenced artists European musicians like Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, who would later become central figures in European jazz.

Through the course of the Great Migration and the years to follow, the Black neighborhoods of Chicago and New York became incubators for prolific jazz innovators and virtuosos. The Black night clubs of Chicago and Harlem served as their proving grounds. All-night cutting contests pushed jazz musicianship to new heights of creativity and expression, and became the basis of Harlem Stride piano. The early contributions of New York jazz composers such as Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson stand as major achievements of the Harlem Renaissance.

The intermingling of cultures in Chicago led to many white musicians gaining a great appreciation for jazz and joining in the tradition. Musicians like Bix Beiderbecke, Frank Trumbauer, and the Austin High Gang drew great influence and inspiration, and directly borrowed techniques from the recently arrived New Orleans transplants. Beiderbecke and Trumbauer and would later go on to make their own worthy contributions to the jazz canon.

LOUIS ARMSTRONG: SHIFTING THE FOUNDATION OF JAZZ

The most influential musician of this migration, and of the first 50 years of jazz music, was cornetist/trumpeter and vocalist Louis Armstrong. The genius and talent of Louis Armstrong represents a seismic, revolutionary event for jazz and American popular music. Louis Armstrong innovated melodic phrasing and singing, and helped to advance not only jazz music, but Western music as a whole.

Armstrong was from New Orleans, where at an early age he built his reputation as one of the best players in the city. He first found more widespread notoriety after moving to Chicago at the promise of employment with King Oliver’s Creole Jazz band. Joe “King” Oliver was a highly influential cornetist in his own right, innovating through the early use of mutes and cups to alter tones and bend pitches in his style.

Once Armstrong joined the band, the group became renowned for their incomparable improvised solo breaks. The band recorded prodigiously—forty-three sides for the OKeh, Columbia, Gennett, and Paramount labels in 1923 alone, producing some of the earliest and best works in the history of jazz. There were original compositions by Oliver, Armstrong, and Hardin, but also works by New Orleans musicians such as A. J. Piron and Alphonse Picou.

Under the guidance and urging of his new wife and King Oliver pianist/composer/bandleader, Lil Hardin, Armstrong improved his personal image and struck out on his own, driven to establish his reputation as “The World’s Greatest Trumpet Player.”

Armstrong moved on to New York and began playing with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra. Armstrong’s refined approach to the hot style of Chicago improvisation raised the bar for the best players in New York City. Armstrong also performed on numerous freelance recordings, often with blues singers, in a wide array of gigs that served to hone his iconic style. After a year with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, Armstrong grew weary of the loose playing and lack of commitment of his bandmates. Louis made the decision to return to Chicago, where he would find a musical peer in pianist Earl Hines, and forever change the landscape of American music.

Back in Chicago, Armstrong formed his landmark group, Louis Armstrong and his Hot Five (and Hot Seven). In the Hot Five sessions with Earl Hines on piano, the group produced an American masterpiece: the monumental 1928 recording of “West End Blues.” Within the first 30 seconds of “West End Blues,” Armstrong established the prevailing sense of swing in jazz rhythm, and revolutionized phrasing and playing technique in jazz music. Louis breaks into a loose scat as a melodic refrain to the trumpet, pioneering the style on recording, and introducing the world to a new era of jazz. Armstrong’s sense of timing and swing and virtuosic playing were unmatched, and rightfully placed him at the forefront of popular music.

In his celebrity status and cultural significance, Louis Armstrong helped define jazz as a fundamentally African American-led art form, and as the first great cultural contribution of the United States to global society. Armstrong’s presence proved to extend beyond the world of music and have a profound impact throughout society.

From the inspiration he provided to Harlem Renaissance figures like poet Langston Hughes, to his later support and involvement in the Civil Rights Movement, to his work as a U.S. Ambassador, and through his career in film, Armstrong became recognized as a culturally significant figure, and as the face of jazz worldwide. His celebrity was unprecedented for a Black musician of his time, and he garnered earnest respect and admiration among his musical contemporaries. He was the first African American to publish an autobiography, first to host a national radio show, and first to get featured billing in a Hollywood film.

Louis Armstrong, through his career-long tightrope act of tact and conscientious efforts, was able to find agency and cooperation with a great degree of success; skillfully navigating the minefield of white conceptions of his identity, the hostile racism of early 20th century America, and the shady business dealings of the mafia-run entertainment industry of the time. By working with white performers, he raised the profile of Black musicians in the eyes of broader American culture, and made clear the undeniable influence of his talent and skill.

The opinion of Armstrong in the Black community would vary in later years, with some of the musicians of the Bebop community accusing Armstrong of being an “Uncle Tom.” Dizzy Gillespie went as far to call Armstrong’s style, the “Uncle Tom Sound.” This deeply offended Armstrong, understandably so, and he would long have a hostile attitude towards the Bebop movement as a result. Armstrong regarded Gillespie’s music, and Bebop in general, as strange and unapproachable, and filled with ideological fervor.

Gunther Schuller, the noted American jazz critic, remarked that “creepy tentacles of commercialism” had laid bare a “wasteland” in Armstrong’s career for more than 40 years. However, the blending of more commercial, European orchestral styles with jazz in Armstrong’s later career would predict the emergence of modernist movements in jazz in the 1950’s, and in crossover and postmodernist styles. In a 1957 lecture at Brandeis University, (the very same) Gunther Schuller coined the term Third-Stream to describe this merging of jazz and classical streams, which Schuller then said represented a new synthesis in jazz composition.

Because of the exploitive roles that he had been placed in throughout the course of his performance and his film career, alongside his switching to more “populist fare” during the Swing era, Armstrong was accused of being a sellout. The status of Armstrong as the symbol of early jazz and the course that his career had taken served as a proxy by which the new generation would understand their relationship with jazz music, and the commercialization that came with Swing and white adoption of jazz.

In the context of the disaffected and disenfranchised Black youth of the time, Armstrong represented everything wrong with jazz, and the malignant illusions of a “separate but equal” society. In the context of history, the youth’s rejection of Armstrong was certainly understandable, while some may consider it misguided. To a good extent, the very act of being a prominent Black jazz musician was revolutionary action in the era from which Armstrong came.

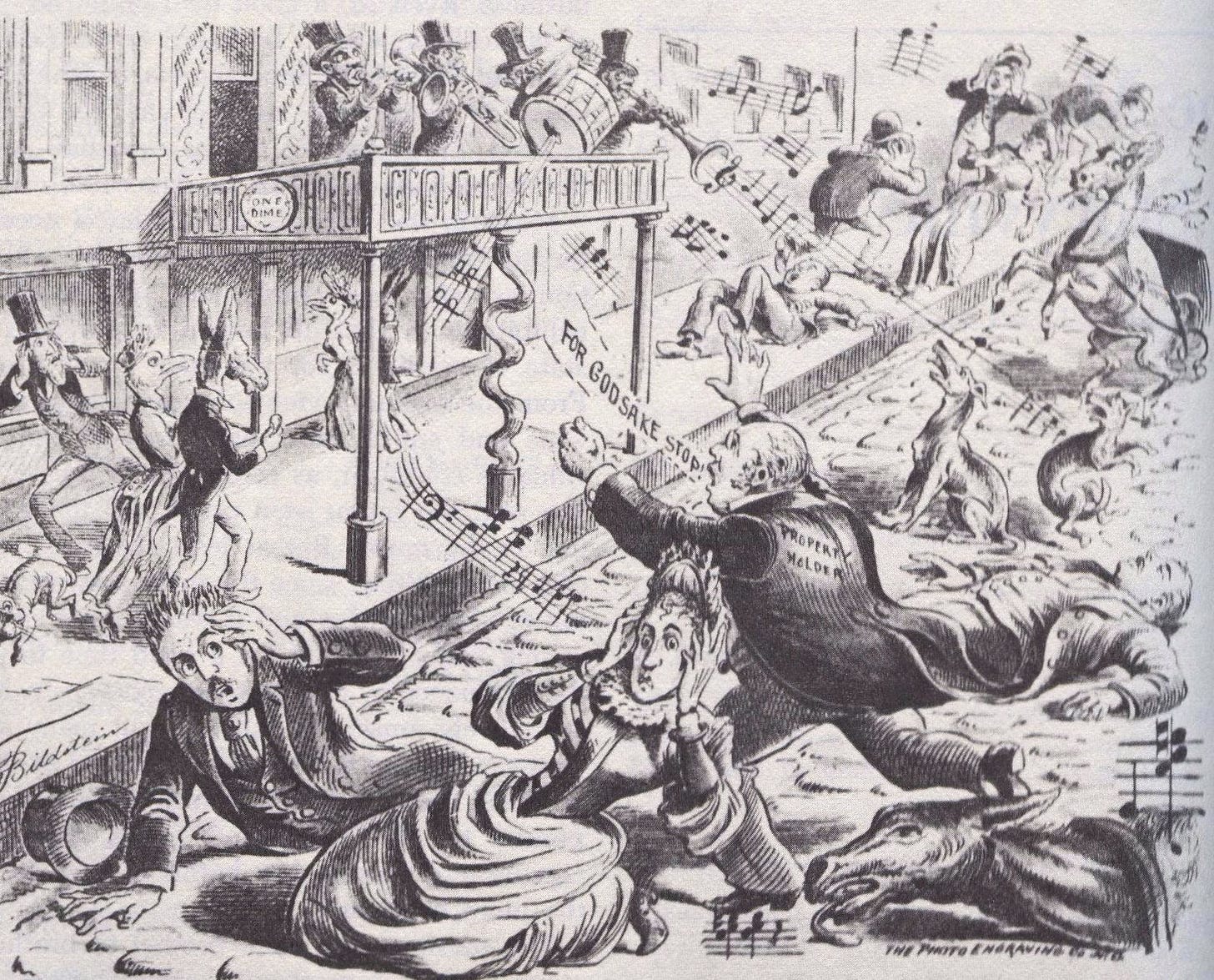

Prohibition Era America, whipped up with religious fervor and strongly against racial intermingling, would scapegoat jazz music for a variety of social issues. Fears of the perceived, illicit, forbidden powers of jazz music were central in the push to outlaw cannabis, and were blamed for the failures of alcohol Prohibition. Chicago specifically had a board of morality that went as far as regulating the types of dancing that were allowed. They blamed jazz music for the popularity of supposedly “immoral” dances, like the dreaded shimmy.

For much of Armstrong’s career, he was a cultural outsider. He was battling through hostile racist conditions of the South in the name of playing his music, standing up for civil rights, running from Chicago gangsters who necessitated armed security, facing legal troubles for smoking weed, and handing out cash on the streets of his hometown.

Though it would come after the first integrated performances of the Benny Goodman Trio in 1936, Armstrong also helped to lead the push for integration, with his integrated All Stars forming in 1947 and including exceptional trombonist and white musician Jack Teagarden. Miles Davis would continue in this practice of hiring the best players, regardless of race, in the decades to follow.

A “sea change” moment in the Civil Rights movement came in September 1957, when Louis Armstrong courageously spoke out in opposition to Arkansas Governor Faubus using the National Guard to prevent nine Black children from entering a white segregated school in Little Rock. “The way they’re treating my people in the south,” Armstrong fumed to reporter Larry Lubenow, “the government can go to hell.” Just a few days later, President Dwight Eisenhower sent the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock to make sure the students made it safely into school.

Many believed Armstrong’s words led Eisenhower to action, as Armstrong’s courageous stance made national headlines. In a conversation with Mike Wallace days later, Thurgood Marshall explained that African Americans “have the full support of the Federal Government,” before noting that “there’s a percentage of Negroes that believes the government action came too late.”

Still, Armstrong’s massive cultural contributions would long go overshadowed by what was seen as his complicity in negative stereotypes of Black people. A more nuanced opinion might see Louis Armstrong as a significant figure of Black History and an early leader of the Civil Rights Movement, whose beginnings in extreme poverty led him to accept career longevity and social mobility over the defense of principles, in an extremely hostile, repressive, and even murderous social environment.

Jazz advanced as a music as the United States advanced as a culture. This conflicting relationship with commercialism, and of commercialism as a symbol for white culture would take different shapes over time, and carry different implications. The ongoing struggle of Black musicians in a society that sought to commidify their abilities without recognizing their humanity would define jazz in the decades to follow. This winding path saw the emergence of new styles of jazz, and new, revolutionary artistic motives. In Part Two, we’ll explore this further as we look at the Swing Era and the Bebop Movement. Til then, keep listening…

Thank you to all those who have read and enjoyed to this point. The following sources were immensely helpful in writing this brief history. I strongly suggest you check them out, as there is so much more to jazz than I am able to cover in this single piece.

Primary Source Material:

Martin, Henry, and Keith Waters. Essential Jazz: The First 100 Years. Schirmer/Cengage Learning, 2014.

Additional Source Material:

Branley, Edward. “NOLA History: Congo Square and the Roots of New Orleans Music.” GoNOLA.com, GoNola, 16 Nov. 2018, gonola.com/things-to-do-in-new-orleans/arts-culture/nola-history-congo-square-and-the-roots-of-new-orleans-music.

Demby, Gene. “The Truth Behind The Lies Of The Original ‘Welfare Queen’.” NPR, NPR, 20 Dec. 2013, www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2013/12/20/255819681/the-truth-behind-the-lies-of-the-original-welfare-queen.

Edwards, Bill. “Benjamin Robertson Harney.” RagPiano.com, 2021, www.ragpiano.com/comps/bharney.shtml.

Gioia, Ted. “The Tragic Story of America’s First Black Music Star.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 18 Oct. 2019, www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/tragic-story-americas-first-black-music-star-180973375/.

Glanton, Dahleen. “The Myth of the ‘Welfare Queen’ Endures, and Children Pay the Price.” Chicagotribune.com, Chicago Tribune, 20 May 2019, www.chicagotribune.com/columns/dahleen-glanton/ct-met-dahleen-glanton-welfare-queen-20180516-story.html.

Huse, Andy, et al. “Summary of The History of Minstrelsy · USF Library Special & Digital Collections Exhibits.” USF Libraries Exhibitions, University of South Florida, 2012, exhibits.lib.usf.edu/exhibits/show/minstrelsy.

Martin, Henry, and Keith Waters. Essential Jazz: The First 100 Years. Schirmer/Cengage Learning, 2014.

Pilgrim, Dr. David. “Who Was Jim Crow?” Who Was Jim Crow?, Jim Crow Museum - Ferris State University, 2012, www.ferris.edu/htmls/news/jimcrow/who/index.htm.

Prideaux, Ed. “Not a Wonderful World: Why Louis Armstrong Was Hated by so Many.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 17 Dec. 2020, www.theguardian.com/music/2020/dec/17/not-a-wonderful-world-louis-armstrong-was-hated-by-so-many.

Riccardi, Ricky. “‘I’m Still Louis Armstrong–Colored’: Louis Armstrong and the Civil Rights Era.” That’s My Home, Louis Armstrong House Museum, 11 May 2020, virtualexhibits.louisarmstronghouse.org/2020/05/11/im-still-louis-armstrong-colored-louis-armstrong-and-the-civil-rights-era/.

Check out the Ken Burns documentaries too, those are great!